The Painting

In which a cherished legacy piece is lost, then found, and then lost again.

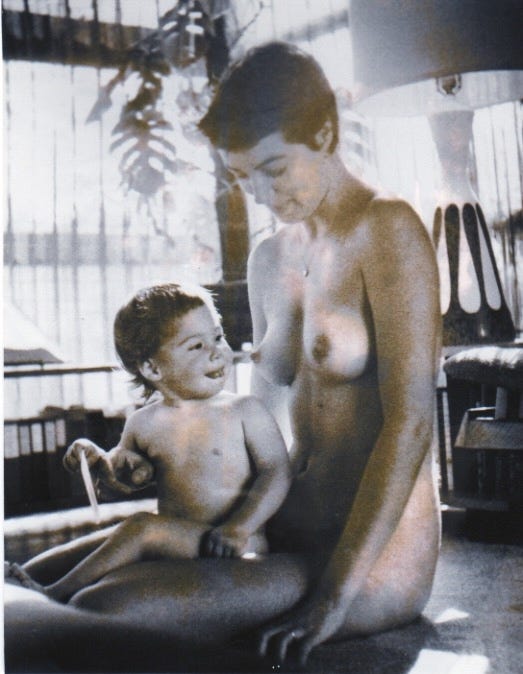

When I was about a year old, my mother had a professional portrait photographer capture an image of the two of us in the classic “Mother and Child” pose, both “bare-assed,” as she would say (see below). The theme of the Mother and Child is ubiquitous throughout the history of Occidental fine art, whether depicting Mary, Mother of God and the baby Jesus or other less exalted folks, like us. I would note here that my mother considered herself a Bohemian and embraced a natural and frequent state of nakedness around our house. (This may have been related to her desire to, whenever possible, showcase her slim and lithe body to anyone in the vicinity.)

Shortly after World War Two, when my father was in Italy making the film “Teresa” with Pier Angeli, Rod Steiger and (an uncredited) Robert Wagner, he met the Serbian-American artist Savo Radulovic. At the time Radulovic was dragging his heels about returning to the USA by working as an extra on the movie. He had been one of a troop of American painters tasked with portraying combat during the war. He and my dad bonded over their mutual love of any and all booze, and became lifelong buddies. I grew up slurping spaghetti with his son, known as “Johnny Radoo.” In 1962, Savo was working out of his studio at 123 E. 62nd Street in New York City, serendipitously the basement of the building where my parents rented a small apartment for most of the 60’s. My father’s work as an actor often took him to the city, and when not in use as a pied-a-terre it was sub-letted to various friends and acquaintances. Savo was tasked with creating a painting from the Mother and Child photograph, and it is not hyperbole to say that this became one of, if not the most prized possession(s) of my mother’s entire life. She also displayed the original photo widely and proudly. During the years that she had completely disinherited me, her only daughter, ie her “Rottenkid,” the painting was the sole item set to be bequeathed to me. Although she demonstrably did not like me for most of my life (see Rottenkid, above), she adored the portrait of us together: perhaps a relic of that sweet innocent time before I had begun to flex my rebellious spirit. A representation of how she wished her world, her identity as a mother, could stay.

After she died in 2011, I spent about a month distributing my mother’s possessions as directed in her estate. By this time I had become, through sheer entropy, her executor; everyone else had died. One day I returned from a respite at home in Central California to pick up the house-clearing project, and discovered the walls of the living room shockingly, obscenely empty. The artwork that had adorned those walls for forty years was gone without a trace, leaving sad squares on the grayish walls—unpainted for decades. A broken window in the dining room, plus a clear footprint of a single, large trainer, showed the thief’s ingress. His/her/their egress was via the front door, where several clear plastic shoeboxes containing women’s pumps had been abandoned in a rush. I was deeply, profoundly shaken; if my mother had had a grave, she would have turned over in it (she donated her body to UCLA Medical School). I balanced my grief gingerly, the loss of the paintings, especially the Mother and Child, like a gut-punch just after the whole-body-blow of her death.

A police report was made, an insurance claim filed. There is an entire department in the Los Angeles Police Department dedicated to the theft of artworks; they told me there was little chance of recovery and not enough clues to locate a perp. Everyone was certain it was an inside job, someone who knew she had passed away and the house was for sale. The insurance paid out about $10,000 for the loss, which I added to the “estate” for distribution amongst the 19 beneficiaries.

Two years later, I got a message from the “LA Art Cop,” as the detective styled himself: Two of the paintings, both by Savo Radulovic and one the “Mother and Child,” had turned up in a pawn shop in the San Fernando Valley. CCTV showed me that it was my mother’s beloved Belizean caregiver who had pawned them. She and I had been like sisters, I’d thought, in the last two years of my mother’s decline. But she’d been unhappy with her financial “haul” in the will and had severed contact with me. After an intense bout of self-reflection, I chose not to press charges. I wanted this toxic, incredibly disturbing event out of my life. Plus, she had a precious and irrepressible daughter, whom my mother had loved. But I did post a warning with the California board of certified caregivers.

My husband and I approached the pawn shop holding hands. I was about to be re-united with a prized piece of my mother’s legacy. But then the pawnbroker pulled the framed canvas out to show, and stated that the price would be $2500. I looked again at this piece of dusty, rather faded art and thought of everything that had gone between my mother and I over the years. My emergence from her vitriolic orbit, the sense of freedom I’d relished without her constant, sapping disdain. And I decided that, no, I did not need this painting back in my life. I could think of more organic, healing uses for $2500. Walking away from that pawnshop empty-handed felt like being released from the final gate of a prison in which I had chosen to incarcerate myself.

And it felt good.

“Did you know that if you tap the ❤️ at the bottom or the top of this email it will help others discover my publication and also MAKE MY DAY?”

Tidbits For The Week of June 18, 2024

Brigit’s What I’m

CURRENTLY LOVING ➡️ The kefalotyri cheese I smuggled back from Athens; it made a fabulous saganaki last night. THINKING ABOUT ➡️ How important is art in our lives, and what do you take with you when and if you downsize? LISTENING TO ➡️ Robert Mitchum's totally bizarre album "Calypso - Is Like So."

What a story! The photo I find slightly disturbing though I'm not surprised that she had it made into art. Sounds like you did the right thing by walking away from it. Love you! xxx

So much of your life is cinematic. This vignette no less so.