My Brilliant Friends

Italian-American Friendship Report (IMO), and The New Refugees

When we were in Puglia and Florence this past March and April, the Italian affection for Americans was mostly in the best of health. There was confusion, shock, and sympathy. Empathy, even (“You know, we have our own problems….Georgia Meloni is no saint.”) I did get pointed questions from folks I interacted with, putting my in-progress Italian to the severe test.

Non abbiamo mai votato per il coglione arancione (grins). No, non sappiamo cosa succederà. Purtroppo, nessuno lo so (sadness).

Now—arguably only to a certain extent—we all know what is happening, even if not what will happen next month, next year, tomorrow.

Last week we visited a simple little restaurant where we have had friendly, mostly inconsequential chats with the owner’s son over several years. We shared with him that, because of unresolved visa issues, we will have to return to the USA for awhile, in about a month.

Loudly: “Go anywhere else! Asia, Africa, anywhere!”

Around the tiny dining room, sympathetic and knowing faces nodded up and down; their eyes darting away from us. We felt ashamed; it was an uncomfortable feeling. Our many Italian friends are less vocally incendiary but deeply concerned, curious, and overwhelmingly fearful. For us—where will we go, what will we do?—and for Italy, Europe, and the World. Especially my Estonian girlfriend, who may have called herself an expatriate but is definitely an immigrant in Italy even after 20 years.

As an American who has traveled widely, constantly, and in a mostly bulletproof cloud, I never thought about the issue of American exceptionalism, but I’m willing to admit I used to take it for granted. Folks in general liked, even loved us Americans. No more. They do still feel sorry for us. I hope that lasts.

For longer than I’ve been alive, the term “expatriate” has mostly been applied to white people from English-speaking countries who move to another country not their own. This has struck me as odd since I was an American “expat” living in the UK in the late eighties, and then an American “expat” living in Spain in the early nineties. What makes an expat an expat, I often questioned? Why doesn’t it apply to all people of all colors and nationalities who live in a country not their own? Back then, this was a niggle; now it’s like sandpaper on a rash.

WE ARE ALL IMMIGRANTS.

The terms expat and expatriate will forthwith be banned from my lexicon and disputed when I hear it uttered. Not easy, since there are so-named clubs all over the world for such fortunate folks. None of them are selling cheap trinkets on the street-corners of Florence.

My mother was an expat in the Bahamas in the 1950’s, and preeningly proud of it. My father was an expat in Mexico City before WW2, and was affectionately known as “Señor Frijoles” because of the way the locals pronounced his real name: “Meester Beans.” Cringe.

Here in Italy, we are immigrants, just like everyone else who was not born and raised here. At some moments of despair about the state of the world, and facing an intransigent Italian bureaucracy, I even think of myself as a refugee. Who will want to take us in, I ponder. Not Ireland (my Irish great-grandmother is too far removed), not Poland (ditto). Portugal has stopped their welcoming immigration policies since too many jumped on their visas. The internet abounds with fake information on easy visas.

Recently I heard Vanuatu would give anyone a passport within 90 days. Vanuatu is really rather remote, but I suppose it’s worth looking into.

Note: None of the food images here were taken at the restaurant mentioned above. I include them as a way toward finding some level of joyful participation in the sorrows of the word, to paraphrase Joseph Campbell—who likely never imagined the concept would be applied to pizza.

Also: I just bought your book, which looks fab!

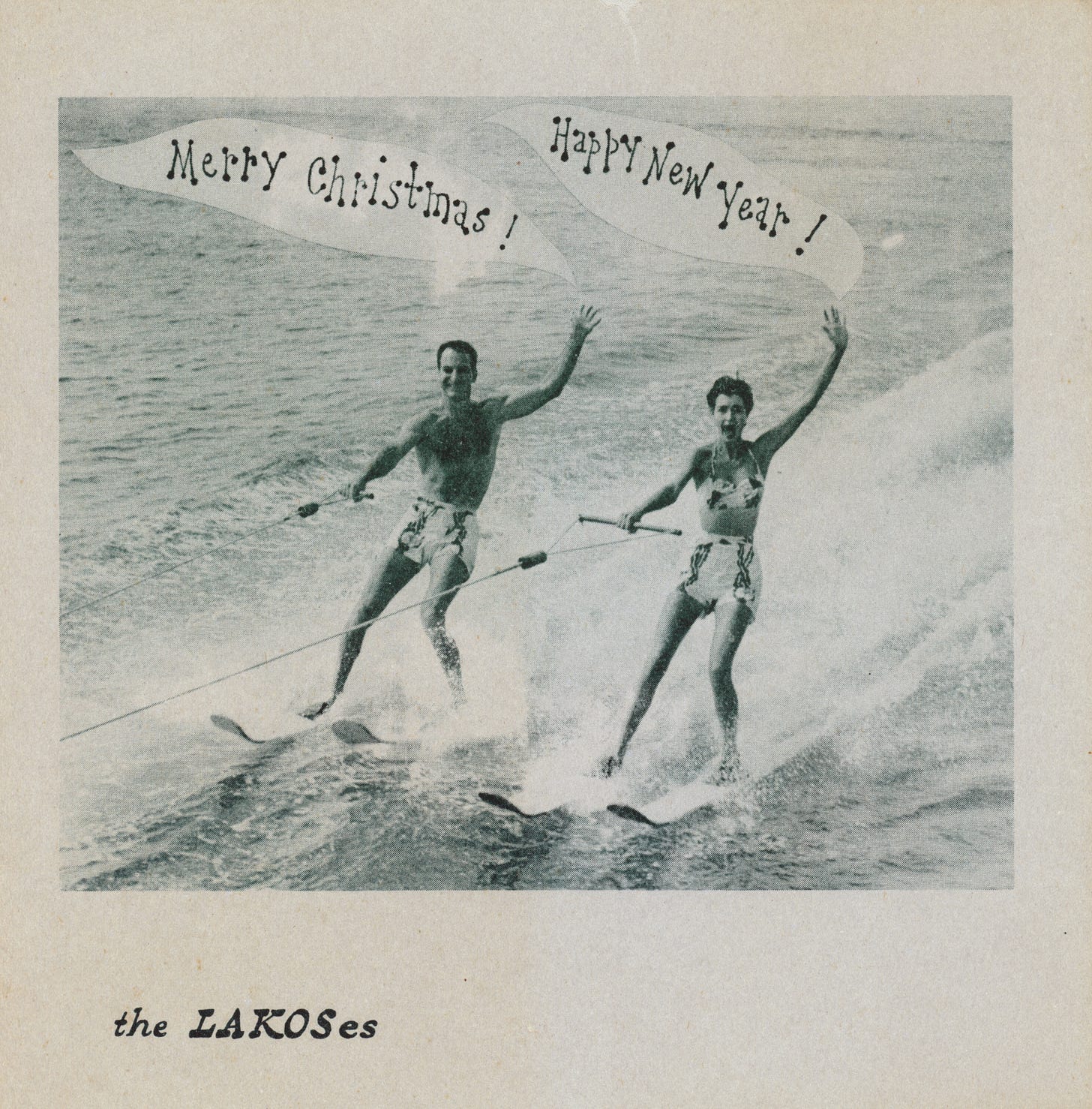

Thank you for jumping on the expat vs immigrant bandwagon; I totally agree. I hope you find a good solution to your visa problem. Love your folks’ greeting card!