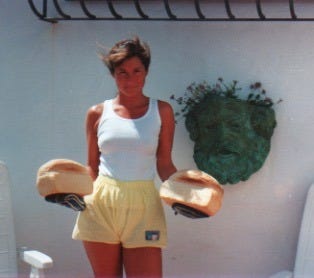

Estepona, Spain, sometime in the last century

The terra cotta-tiled terrace had a 320° view of the Mediterranean; across all that glassy-smooth water, you could see Africa. It was off the little living room with its inefficient fireplace, the one I’d been fighting with from my arrival in freezing-cold March (when I realized “someone,” i.e. me, had neglected to install a heating system in our new house), to mid-May, when it was temperate for about five minutes before shooting rapidly up over 99°. We’d moved from England together, my first husband and I, to find a simpler life after he’d been fired in disgrace from his ritzy investment banking job (unfairly, I feel compelled to add). He had suddenly become a very small fish in their very large pond; according to him, staying in London was not a possibility. His agenda: to lick his wounds. Mine: to embrace the positive side to this new development, to bloom in the warmth of the sun and richness of the culture, food, and wine.

The waiting list for a home telephone was rumored to be about four years long. What’s an internet?

The house was starting to feel finished, but the lawn was still just a hill of dead-looking, little brown sprigs of someone else’s lawn. That’s how you make a new lawn in Southern Spain: snip about 300 little pieces of the viny, weed-like plant that serves as grass in this sauna-like climate, then stick them in the dirt, and add water. Every day. At first, they all appear to die, then after a few weeks, magically, each one sends out a hopeful green runner; eventually the runners overlap and look like a netting of pretty green lace over the brown, sandy dirt. At some point, months down the road, there are enough runners to completely cover the ground. But now, of course, they’re off and running in mad abandon, and you have to start trimming them. (Note that I did not say “mow.” At first you use scissors.)

My time in Spain had already begun to change my cooking habits, especially when it came to the ingredients. Butter, cream, and red meat were showing up less often; salads, fish, and vegetables had begun to assume a greater role. The markets on the coast were strong on cabbage, potatoes, onions, peppers, and tomatoes, weak on exotics such as arugola and fennel, and romaine was in good supply. So I planted what I needed, using seeds collected on the drive down through France: green and yellow zucchini, arugola, mesclun, flat-leaf parsley, chives. A nursery on the road to the village of Ronda supplied me with woody herbs like rosemary, sage, and oregano, and they quickly, gloriously, made themselves at home. The hill behind the house was already covered with wild thyme, and besides providing my kitchen with aromatic ammunition, it became a favorite place for my Staffordshire Terrier, Wiggy, to snarfle and root around for hours, thereby imbuing herself with the green and vegetal scent and winning the title “Wild Thyme Wig.”

Now it was summer, and I was giving a simple little dinner on the terrace. You see, in the winter, there was no one around to invite—at least, at that point we hadn’t met any locals yet. But that first summer brought all the English friends down to the Costa del Sol. It was important for me to prove that this sudden move to Spain and profound financial change-of-life hadn’t affected my ability to set a fine table and create—at least occasionally—a simpatico evening. The first of many, many crops of arugola was up and ready for snipping. Having found the local bakeries’ bread to be bland—at first crumbly, and then rock-hard by nightfall—I’d created a sourdough starter using directions found in Chez Panisse’s pink book, and begun baking my own bread. It was chewy and sour and paired perfectly with the superb Ybarra olive oil I could easily pick up at the Hïper-Coop.

For this dinner, we’d be six at the table, which was set with local blue and white Granada-pattern ceramic plates, sprigs of lavender, and several glass buckets of ice and icy-cold Viña Sol. Two of our very closest friends—who were still reeling in shock at our precipitous departure from London a few months earlier—would be attending.

The menu—in my mind, at least—was to be rustic yet refined: it included sautéed boneless duck breasts and individual potato rösti. A good rösti is crusty, golden, and oily; the duck breasts, when cooked for at least 10 minutes with the skin side down, have a similar crusty, golden fattiness. In order to achieve all this crustiness, a great deal of high-heat searing is required. And it must take place quite close to serving time, or the duck skin will take on the consistency of a sun-baked tire, the rösti begin to sweat, turn grey, and morph into a substance that could be used to apply wallpaper.

Air conditioning had yet to arrive on the coast, and at about 7pm the thermometer was pushing 100°. I showered, dressed, and put on some makeup. I was wearing my first new outfit since the move, a gauzy little skirt with several layers of eyelet petticoats and a bandeau top that I had found in Puerto Banus, the garish slice of jet-set society down the coast. I was starting to feel proud of my new life in Spain. Sure, I could roll with the punches, I thought to myself. Outside my kitchen window there was a wrap-around view of the Mediterranean; I could just make out the flickering lights of Morocco across the water as the golden path of the sunset faded to a smoky blue.

Then I started frying. Six duck breasts and six rösti. I had four large skillets going at once, and at first I played them like an instrument, adjusting the heat under one while I pressed down on the rösti in another with a flat spatula, to force more of the potato mixture into contact with the sizzling-hot pan. The duck breasts were beginning to throw off a remarkable amount of smoke, but I couldn’t reduce the heat or they’d end up poaching. I had neglected to install an extractor fan. Soon the process began to feel less like a virtuoso performance by a talented musician and more like a horrible gauntlet, a journey into hell where I could not step away from the stove for even a moment. To say that I was sweating at this point is an understatement.

When the guests arrived at 9, dressed to the nines—as is the custom for the English in Spain—they were greeted by a character out of a Fellini movie. My makeup was running in rivulets down my face and my hard-won suntan had gone pasty white in what I imagine was the first phase of heat stroke.

After I served my polite but stunned guests, I dove into my first glass of wine, which served to relax me not in the slightest. Oh, yes, Brig, you’re really getting a handle on the relaxed Spanish lifestyle.

The rösti was golden and crisp on the outside, tender and creamy-pale within. The duck breasts sported an overcoat of deep, dark-brown and crunchy, toothsome skin atop a thin layer of white fat. Inside, they were pink, meaty, and juicy. Dessert was an apple soufflé, just in case the kitchen wasn’t hot enough already. It would have been a fantastic menu for a fall evening by the fire. Nice, sure, but it was the first time I’d ever seen this particular group of friends depart a dinner party in such somber mood. Just providing good food for my friends, it seemed, was not enough. I came to understand that if I, the cook and hostess, was stressed and uncomfortable, my guests could not enjoy themselves either.

One of the lessons here was obvious. In an act of self-defense, I learned very quickly: my mantra became “cook in the morning, relax in the evening.” Get all the work out of the way while it’s still cool, then refrigerate the food until an hour or so before serving. Far from feeling like a compromise, this approach revealed a whole world of rustic food that, in my first years as an ambitious cook, I could never have imagined. And it’s served me well no matter where I lived, from Venice Beach to New York’s Hudson Valley to Paso Robles, California—because as I moved along, I realized I didn’t want to be frying rösti ten minutes before my guests arrived no matter what the weather.

Given a choice, who wouldn’t prefer to sip a chilled glass of rosé and nibble radishes and olives while the flavors of a few previously-cooked (or never cooked at all) dishes mingle and mature, unattended, in the kitchen. Just waiting, politely, until you are ready to serve them.

(Adapted from The Relaxed Kitchen: How to Entertain with Casual Elegance and Never Lose Your Mind, Incinerate the Souffle, or Murder the Guests, by Brigit Binns; a few elements of the essay also appeared in my recent memoir, Rottenkid: A Succulent Story of Survival.)

“Did you know that if you tap the ❤️ at the bottom or the top of this email it will help others discover my publication and also MAKE MY DAY?”

Tidbits For The Week of October 21, 2024

Brigit’s What I’m

CURRENTLY LOVING ➡️ Studying Italian (B1 level—yay!) with my spectacular teacher, Debora. THINKING ABOUT ➡️ How to survive the next 14 days without losing my mind. LISTENING TO ➡️ Angel from Montgomery. I swear, it always calms me down.